One of the most common—and most expensive—mistakes in AI projects starts with this sentence:

“We’re doing AI, so we need the most powerful GPUs available.”

The real question is:

👉 Are you training models, or are you running inference?

They may both be called “AI workloads,” but their hardware requirements live in completely different worlds.

One-Sentence Takeaway

The true dividing line in AI hardware selection is not model size or brand—it is whether you are doing training or inference.

Once this is clear, many hardware decisions become obvious—and much cheaper.

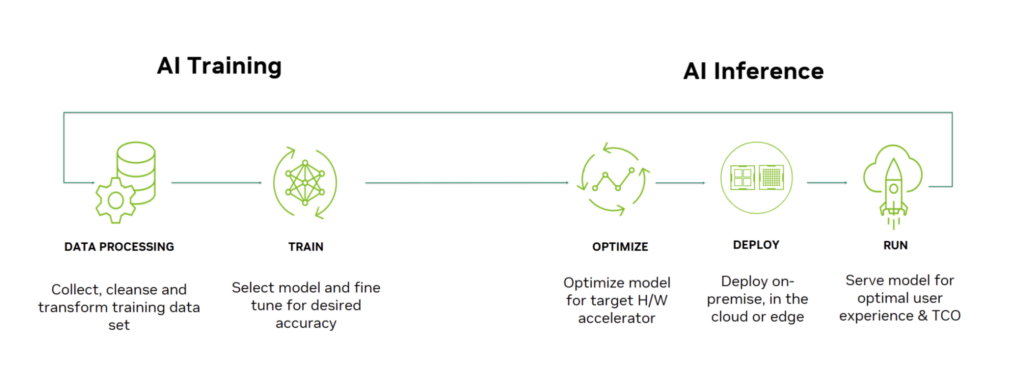

First, Define the Two Phases Clearly

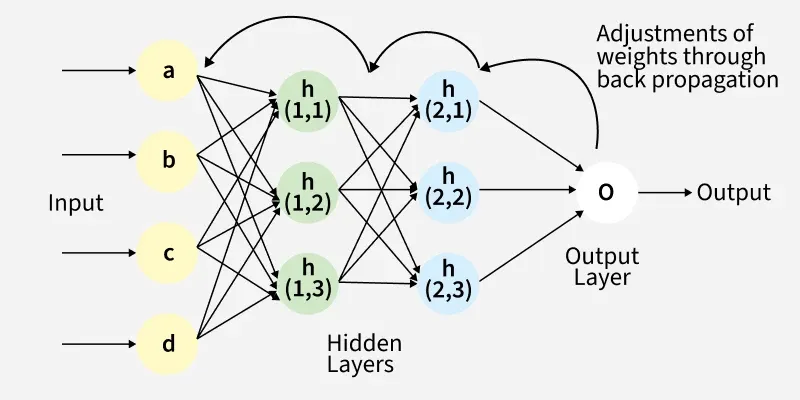

🧠 Training

- Purpose: Teach the model

- What happens:

- Forward pass

- Backward pass (backpropagation)

- Weight updates

- Characteristics:

- Extremely compute-intensive

- Long-running (hours to weeks)

- Designed for maximum throughput

💬 Inference

- Purpose: Use the trained model

- What happens:

- Forward pass only

- No weight updates

- Characteristics:

- Lower compute per request

- Extremely latency-sensitive

- Must be stable and available long-term

👉 Different goals create different hardware priorities.

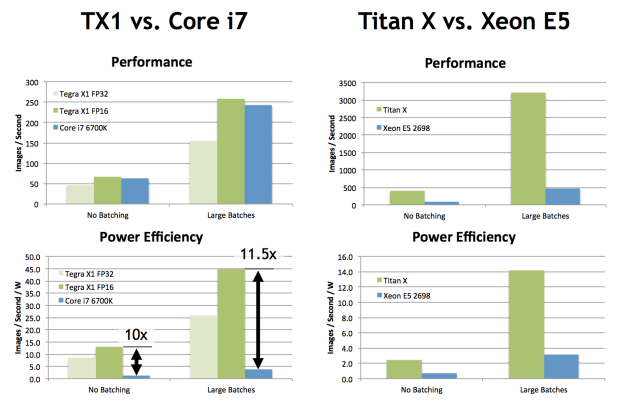

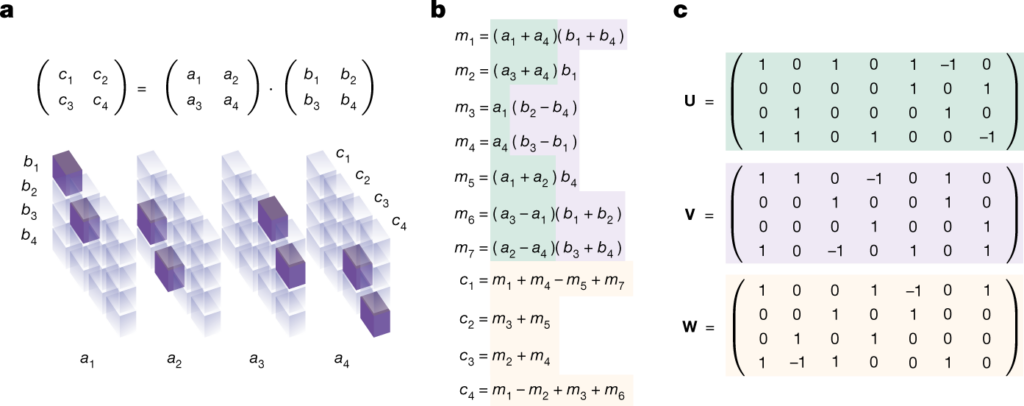

Why Training Is Compute-Driven

Training workloads are dominated by:

- Massive matrix–matrix multiplication

- Backpropagation (often doubling compute cost)

- Repeated execution at full utilization

Training hardware prioritizes:

- Raw GPU compute (FP16 / BF16 / FP32)

- Large numbers of GPU cores

- Multi-GPU scalability

- Power delivery and cooling capacity

📌 In training, stronger hardware directly reduces training time.

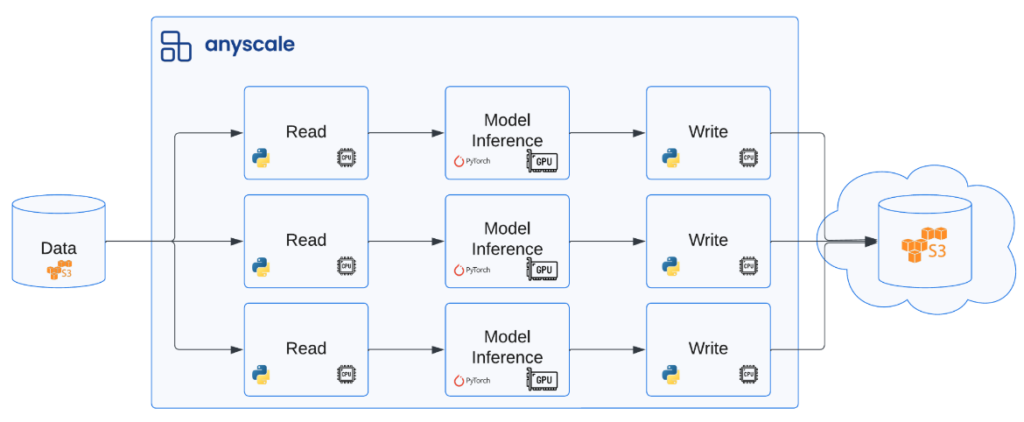

Why Inference Is Memory- and Efficiency-Driven

Inference workloads behave very differently:

- Tokens are generated sequentially

- Attention relies on stored context (KV cache)

- Response time matters more than peak throughput

- Systems often run 24/7

Inference hardware prioritizes:

- Memory capacity (VRAM or unified memory)

- Latency stability

- Energy efficiency

- Deployment and operational cost

📌 In inference, “fast enough and stable” beats “fastest possible.”

The Core Difference in One Table

| Aspect | Training | Inference |

|---|---|---|

| Primary goal | Learn the model | Use the model |

| Computation | Forward + backward | Forward only |

| GPU compute demand | Extremely high | Moderate |

| Memory importance | High | Critical |

| Latency sensitivity | Low | Very high |

| Hardware flexibility | Mostly GPU-only | CPU / GPU / NPU |

| Cost profile | High upfront | Long-term operational |

Why Hardware Choices Often Go Wrong

Because training and inference are treated as the same problem.

Common mistakes:

- Using training-grade GPUs for personal or departmental inference (overkill)

- Expecting inference-oriented hardware to train large models (impossible)

- Comparing FLOPS instead of memory behavior and latency

- Ignoring concurrency and service patterns

A Practical Decision Framework

Ask these three questions before buying hardware:

- Will I train models myself?

- Yes → Training-class GPUs matter

- No → Skip training requirements entirely

- Is this for a single user or a service?

- Single user → Memory and efficiency matter most

- Multi-user → Concurrency and stability dominate

- Do I care more about peak speed or long-term experience?

- Peak speed → GPU cores and compute

- Experience & cost → Memory, efficiency, architecture

The One Concept to Remember

Training is about building the model.

Inference is about serving the model.

Building requires brute force.

Serving requires space, efficiency, and stability.

Final Conclusion

The real divide in AI hardware selection is not model size, not vendor, and not benchmarks—it is whether your workload is training or inference.

Once you understand this:

- Hardware spending becomes intentional

- Architecture design becomes clearer

- AI systems become easier to scale and maintain